Integrity report

Petrol is not a personality: a manifesto for (bio)diversity

Words by Anna Sulan Masing

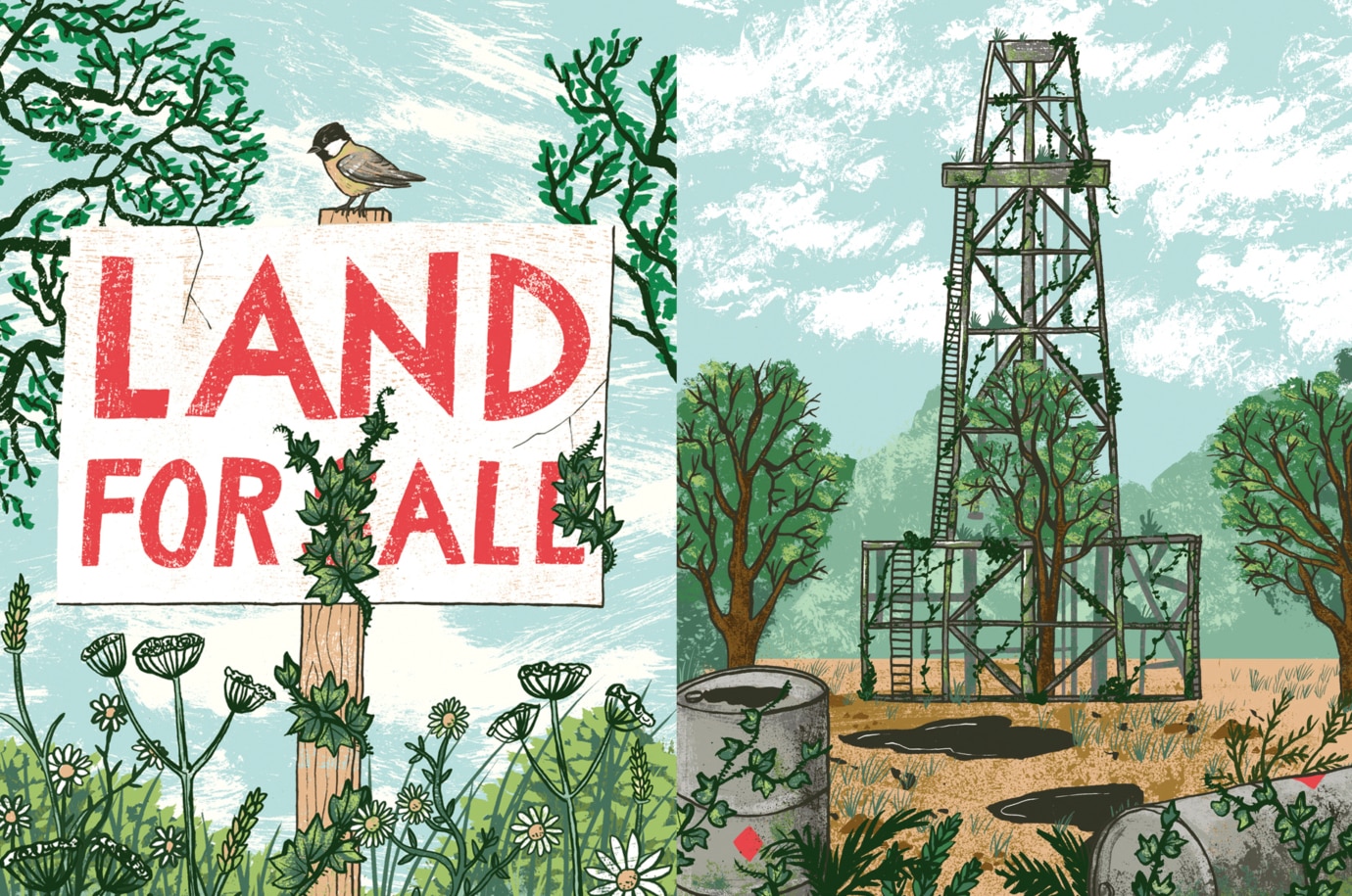

Illustration by Tom Jay

The heady mix of repressed sexuality, colonial structures and binary gender norms all perk up when the topic of the environment and sustainability percolates. I blame the Victorians. In the 1800s, as industry chugged along into the narrow tunnel of capitalism, the concept of diversity— in thinking, in being, in action—was left behind in favor of capital progress, which has been so detrimental to addressing the issues of climate change.

The colonial structure of food and trade—refined in the Victorian Empire and embedded in the contemporary—exhausts the land in its thirst to consume. This is all without the idea of balance and stewardship, which in turn creates the haves and the have-nots, dividing communities and nations. When thinking about diversity it is important that we don’t just focus on representation: this can become a box-ticking exercise that sets up divides, thus continuing ideas of binary. Diversity is about including a range of thoughts, and approaches, and moving away from a linear narrative. By understanding the damage of binary language, identities and practices, we can nurture something new.

Climate deniers come in various forms, but a certain cohort has been of particular interest to a number of environmentalists due to a growing sense of toxic power they seem to hold on the media in the global north. The academic Cara New Daggett has coined the phrase ‘petro- masculinity’ when describing this particular segment of society: spearheaded by the likes of far-right group Proud Boys, this cohort hang on to a make-believe concept of gender and masculinity that is rooted in a bygone era and upholds binary identities and language—concepts of opposition—without any space for diversity. They wrap themselves around ideas such as testosterone being so sacred that masturbation is advised against; they view fossil fuel burning— like owning a big pick-up truck—as the definition of masculinity. So we are forced to watch as these men-children wreak havoc on the planet through acts of rebellion that are ruinous for all, littering lands with phallic oil rigs in a show of power. It is a minority, but it is a loud minority: they regularly capture headlines and recently found themselves deeply embedded in the Trump administration. If their narrative continues to build, one day we may not be able to see anything else.

So what do we do to combat this? Well, all around us are diverse structures that work. The very nature of, well, nature, is that it thrives—we thrive—when not trapped in binary identities. We thrive when we move away from hierarchy to develop inclusive and diverse thinking that is about the multiple. Let’s look at what true (bio)diversity is, and how it can help us move forward.

#1 VENUS IN FUNGI: HONORING A WIDER WORLD

If we look to nature, we can see multiple examples of structures focused on creating and nurturing diverse connections—and complicated ones at that. In his book Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds, and Shape Our Futures, the writer Merlin Sheldrake views these structures as an act of collaboration, stressing the importance of building different networks to grow and develop. “Plants only made it out of the water around 500 million years ago because of their collaboration with fungi,” he explains. “Fungi weave themselves through the gaps between plant cells [...] to help defend plants against disease.” In this sense, it is an act of supporting, and Sheldrake notes how certain fungi are promiscuous in their engagement, resulting in vast, complex systems.

In 1997, a study was published by forest ecologist Suzanne Simard with the phrase ‘Wood Wide Web’ to describe the relationship between plants. I don’t mean to conflate the internet web and plant web (the internet, after all, being a space in which petro-masculinity types spew many of their narratives), but rather to show the effectiveness of a network. The important point is that the network embedded by fungi—or plants—is about new growth, new futures and collaborating outside its kind.

Elsewhere, Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing looks to the fruit of the fungi in her book The Mushroom at the End of the World: On The Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. When examining the particular case of the matsutake mushroom, she demonstrates how, when it gets to the import warehouse in Japan, it has no connections to “pickers and buyers”, let alone an ecological lifeworld. “For a moment,” she argues, “they are fully capitalist commodities.”

It is the lack of connection that allows the mushroom to have this identity—as a commodity— and we are lulled into believing this is important. “During most of the 20th century many people—perhaps particularly Americans— thought that business carried forward the pulse of progress,” says Tsing. But what is that progress if it is devoid of people; who is it serving? In response, Tsing shows that the mushroom is part of a much wider world—part of the pickers, the foragers, the web of hands the mushrooms pass through.

Chris Newman of Sylvanaqua Farms, a farm that is based on practices of Newman’s heritage (his mother is Black and his father belongs to the Piscataway Conoy Tribe), writes in a 2020 essay Indigenous Agriculture: It’s Not The How It’s The Why on the importance of language with regards to connecting with a wider world. He explains how Indigenous languages in the US are verb-heavy, meaning that they create “a world of relationships, actions and stories”, in contrast to English which prioritizes “things”.

These Indigenous languages are being ‘lost’ and with that, an approach to the world that is encompassing and interconnected is also lost. Because of this, as Newman points out, the “colonizer” (white America) has an “extractive worldview, based on private property, personal enterprise, individualism and consumerism”.

Newman give the example of xàskwim monocultures - of corn fields - which were part of a carefully managed ecosystem, including things like “semi-wild plants coaxed into productivity with abundant forest edges and open understories” to create a transformative space. This is in opposition to the colonizer’s approach which takes the idea and creates the Corn Belt.

This further outlines how ecosystem farming then gets appropriated and its transformative power is neutered. To address climate change we need to be transformative. !

#2 THE LAND: ACTUALLY, AN ACT IN DECOLONIZING

Once we begin to examine these ideas—of creating networks, building relationships—in the context of addressing environmental issues it becomes clear that our world is built on the prioritizing of limited voices. It isn’t open mic night.

In 1920, women in the US were technically given the vote. But this isn’t the whole truth. Federal suffrage was only extended to Native Americans of both sexes in 1924 and the Voting Rights Act in 1965 was when, in practice, Black women could vote. This means that for the first time all Americans were allowed to vote—to have a say in the governance o’er the land of the free and the home of the brave!—was only 56 years ago. When we think about the environment, the land we live in and on, we see that inequality is entrenched because of this: only certain people are allowed a stake in this terrain.

In Jane M. Jacobs’ article, Earth Honoring: Western Desires and Indigenous Knowledges, there is a push to understand environmental issues beyond the Western knowledge. “Alliances have developed between feminists, environmentalists, and [Australian] Aborigines seeking to have their interests in land recognized,” Jacob explains.

It is important to note—which Jacobs does—these connections are complex. Some individuals may occupy multiple identities. But Jacob explains that the act of breaking down boundaries is key to “the path to global survival”, while acknowledging that said path “travels across a terrain marked by inequality”.

If we look at this idea of terrain, literally, we can investigate those inequalities more thoroughly. The dominant notion is tied to a colonial idea centered on ownership: google ‘land’ and it is full of ‘land for sale’, registering land with the government, and property searches.

So who owns the land—who has a say in it? To approach these questions, we must first decolonize our thinking about the environment. In Karin Amimoto Ingersoll’s book Waves of Knowing, she writes: “The process of decolonization or of postcolonial development and politics becomes a (re)establishment of indigenous geographical identity, [...] a (re)vitalizing of indigenous geographic identity through knowledges of and relationships with place.” This idea of ‘re’ is because decolonizing is to look to the past, but to do it without nostalgia—so that you are creating new-ness too.

These are big topics, and require huge collective shifts in thinking, but this is to say, when it comes to thinking about the environment, we must nurture a relationship with the past that is allowed to be complicated; allowed to examine the inequalities. Giving space for complication is allowing for diverse thinking to be heard, opening up a way to challenge the growing wave of climate denial.

#3 CLIMATE IS CULTURE: NURTURING A NEW STORY

But what does this all actually have to do with the environment? It is easy to slip into the idea that tackling the changing climate, or to building sustainable businesses, is about capital and science. But really it is about culture. It is people, it is communities, it is identities. When viewed in this light, it is easy to see how fraught the topic is.

The academic Kari Marie Norgaard defines climate change as a ‘cultural trauma’—a process that systematically disrupts the cultural and social. It is through this idea that denial (from the

likes of the petro-masculinity cohort) can be understood. In the 2019 paper Avoiding Cultural Trauma: Climate Change and Social Inertia with Robert J. Brulle, Norgaard explains that denial is centered on “the development and promulgation of climate misinformation”. It’s fake news. It is rooted in corporations, fossil fuel and the status quo.

The existence of climate change, and the need to develop sustainable practices to survive, directly challenges the social status and identity of climate-deniers. Events such as extreme weather caused by climate change do not create cultural trauma. Rather, as Brulle and Norgaard explain, cultural traumas are “socially constructed narratives” that dispute “the existing social order and notions of collective identity”. What this points out is that this collective identity is constructed, and therefore we have the ability, and the power, to rewrite our cultural narrative. We can move away from trauma. To construct a new narrative, we cannot continue centering the story of capitalism, or consumption, as an identity for people to cling on to in desperation. Petrol is not a personality.

Developing networks that focus on multiple connections and relationships allow us to move away from the idea of a center, and thus help us move away from the binary. How we actually

achieve that isn’t just about hiring diverse people and opinions, either.

It isn’t just about empowering people to speak up and change structures. It isn’t about ‘sharing the mic’ when the mic was not yours to begin with. It is about nurturing diverse talent so that they themselves go into ownership. It is building a story with many central characters, all of whom are very different.

It is also about understanding that ‘ownership’ is not a static or singular, but rather a force and a web that allows change and growth—one that is framed around the wellbeing of people and culture. With this refocus we can build structures that support both people’s environment and livelihoods through the strength of relationships. We then have the power to place people at the heart of solutions and stories, we begin to address the limitations of capitalism, and build equitable structures for the future.

I am not advocating for the business world to become a bonk fest, but I am suggesting that, like those fungi, we do take on more promiscuous structures to prioritize multiplicity in relationships. We need to move away from the linear, the binary, the hierarchy. We need to move towards complexity and collaboration.